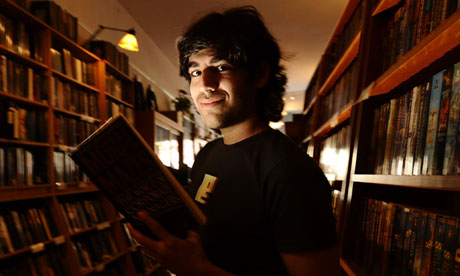

Aaron Swartz, the US hacker and internet

activist who killed himself earlier this month. Photograph: Noah

Berger/Reuters

On 11 January, a young

American geek named Aaron Swartz killed himself, and most of the world paid no

attention. In the ordinary run of things, "it was not an important failure".

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along

But Swartz's death came

like a thunderbolt in cyberspace, because this insanely talented, idealistic,

complex, diminutive lad was a poster boy for everything that we value about the

networked world. He was 26 when he died, but from the age of 14 he had been

astonishing those of us who followed him on the internet. In 10 years

he had accomplished more than most people do in a lifetime.

In the days following his

death, the blogosphere resounded with expressions of grief, sadness and loss not just

from people who had worked with him, but also from those who only knew him from

afar – the users of the things he helped to create (the RSS web feed, social

news websites, the Creative Commons copyright

licences, for example), or those who had followed his scarily open and thoughtful blogging.

What lay behind this anger

was United States v Aaron Swartz, a

prosecution launched in Massachusetts, charging Swartz with "wire fraud,

computer fraud, unlawfully obtaining information from a protected computer and

recklessly damaging a protected computer". If convicted, he could have faced 35

years in prison and a $1m fine. The case stemmed from something he had done in

furtherance of his belief that academic publications should be freely available.

He had surreptitiously hooked up a laptop to the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology network and used it to download millions of articles from the JSTOR

archive of academic publications.

Even those of us who shared

his belief in open access thought this an unwise stunt. But what was truly

astonishing – and troubling – was the vindictiveness of the prosecution, which

went for Swartz as if he were a major cyber-criminal who was stealing valuable

stuff for personal gain. "The outrageousness in this story is not just Aaron,"

wrote Lawrence Lessig , the distinguished lawyer who was also one of Swartz's

mentors. "It is also the absurdity of the prosecutor's behaviour. From the

beginning, the government worked as hard as it could to characterise what Aaron

did in the most extreme and absurd way. The 'property' Aaron had 'stolen', we

were told, was worth 'millions of dollars' – with the hint, and then the

suggestion, that his aim must have been to profit from his crime. But anyone who

says that there is money to be made in a stash of academic articles is

either an idiot or a liar. It was clear what this was not, yet our government

continued to push as if it had caught the 9/11 terrorists red-handed."

What has happened, in fact, is that governments which since 9/11 have presided over the morphing of their democracies into national security states have realised that the internet represents a truly radical challenge to their authority, and they are absolutely determined to control it. They don't declare this as their intention, of course, but instead talk up "grave" threats – cybercrime, piracy and (of course) child pornography – as rationales for their action. But, in the end, this is now all about control. And if a few eggheads and hackers get crushed on the way well, that's too bad. RIP Aaron.

No comments:

Post a Comment